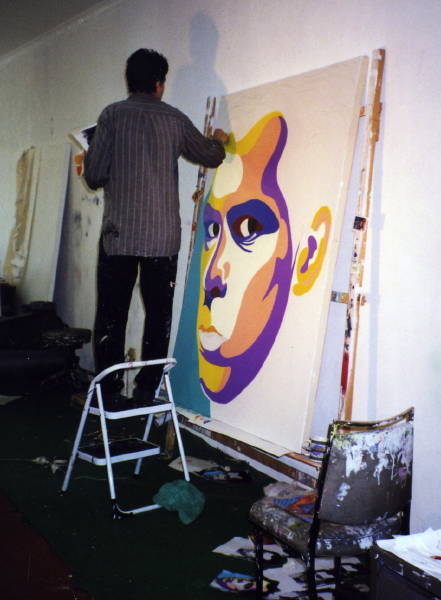

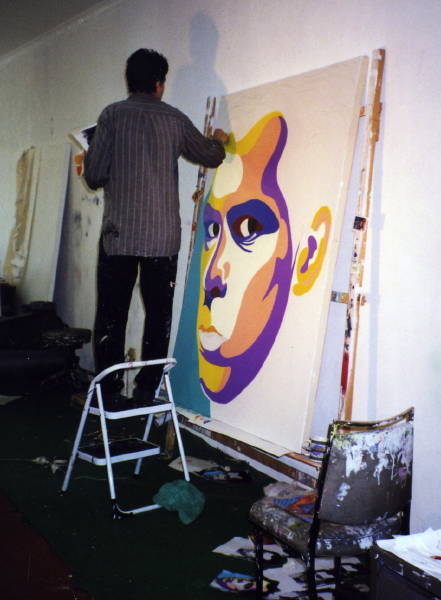

(photo: Arkley at work on Nick Cave [archive photo taken by Alison Burton])

The final months of Arkley’s life, as various commentators have pointed out, were a blur of activity, marked by major success, and then – just at the height of his international fame – his sudden death from a drug overdose, less than a week after returning from the United States. Wise after the event, one might think his life had spiralled completely out of control, but he had been making detailed plans for future projects while he was overseas, and had good reason to feel fulfilled and optimistic as he approached his 50th year.[1]

Early in 1999, Arkley was working flat out on a series of significant works:

- the commissioned portrait of musician Nick Cave for the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra (the finished work was featured on the cover of the April 1999 issue of Art Monthly Australia)

- completion of the four new panels to be added to Fabricated Rooms for its Venice installation

- the set of eight new canvases for his show in Los Angeles in July/August

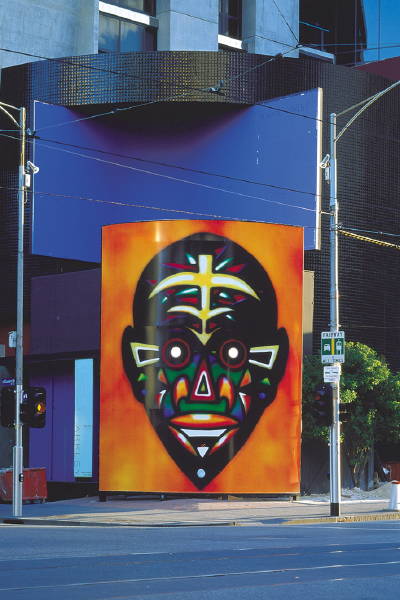

- and various other projects, including plans for a large mural version of his Zappo Head for Melbourne’s Republic Tower (subsequently exhibited, as planned, in October 1999).

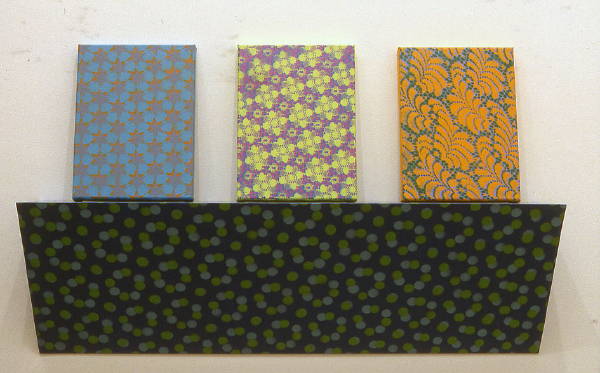

In April, he submitted a new furniture installation to the 1999 Clemenger Contemporary Art Award (won by John Nixon). Arkley’s piece, Homezone (1999) [3/M], like many of his other late works, possesses both confidence and elegance; the work echoes his earlier furniture pieces, but now with considerably more style and sophistication. As Jenepher Duncan put it, in the essay she wrote for the Clemenger catalogue, Arkley ‘has turned the “kitsch impulse” of his work into a personal creative aesthetic’ – an insightful remark that could serve as a summary of his entire career. [2]

Media coverage gathered momentum ahead of the Biennale. Arkley featured in several profiles, including in-flight magazine articles for Qantas and United Airlines.[3] Arkley and Alison Burton arrived in Venice late in May, ahead of the official opening of the Biennale on 12 June. His show, backed by clever marketing by Global Art Projects, was a significant success, and his work attracted substantial attention: see now separate entry on the exhibition. He threw himself enthusiastically into the heavy schedule of media appearances, which included a notable encounter with British Prime Minister’s wife Cherie Blair, recorded for British TV (see now Wyzenbeek 2000). He also met visiting family members, friends and colleagues in Venice, and enjoyed the experience, apart from the heat.[4]

(photo: Arkley with Alison Burton and Corbett Lyon at the Australian Pavilion, Venice, June 1999 [photo: GAP])

While still in Venice (15 June), Arkley received an email, via the Australian Pavilion, from Leo Schofield, Director of the Sydney Festival planned for January 2000, asking whether he would be willing to participate in a plan to illuminate the Sydney Opera House ‘in a manner similar to that used in your Home Show pictures’. Apparently, Arkley was enthusiastic, and the idea was still being mentioned in the press after his death, although it failed to materialise.[5]

After Venice, Arkley and Burton travelled briefly in Italy, and then went to London, where they met colleague Tony Clark, who recalls Arkley’s excited response to visits to historic houses, and enthusiastic comments on plans he was hatching for future decorative projects (quoted in Spray [2001]:142). The two artists had actually been involved for several years in a collaborative project (unfortunately, unfinished), along similar lines: see now Carnival 140-41. While in London, Arkley also met Nick Cave about a future album cover project (Preston 2002: 226-7), and was photographed in a series by Robert Whitaker: for an example of one of these ‘Whitographs’, see Spray [2001]: 146.

Arkley and Burton then toured Ireland, making a pilgrimage to see the Book of Kells in Dublin, and generally unwinding after the frenetic activity of the previous few months. In England and Ireland, they collected source material, and Arkley continued to plan new works. Among the material he collected in England, for example, was a Sunday newspaper supplement on home improvement, including a diagrammatic representation of a renovated terrace house.[6] In Ireland, he and Burton both collected books on traditional Irish decoration and patterning.

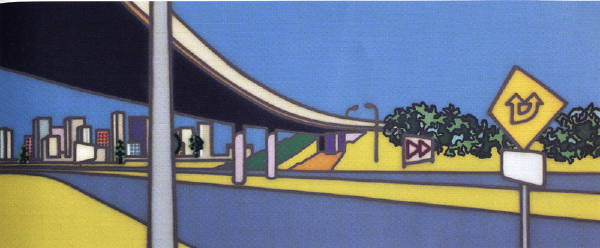

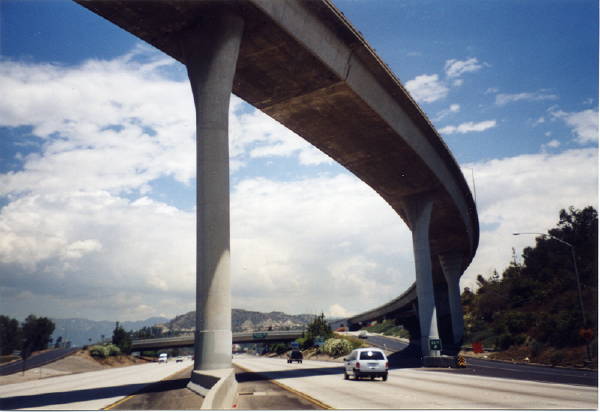

Then it was off to Los Angeles, for the final engagement of the tour – Arkley’s first solo commercial show overseas, at expatriate Australian Karyn Lovegrove’s gallery. The show opened on 9 July, and was both a critical and commercial success: see now exhibition entry. In LA, Arkley and Burton were chauffeured around by younger Australian painter Callum Morton, who recalls with amused affection Arkley’s sorties in search of new freeway source material (see Spray [2001]: 5); cf.Photographs of Los Angeles Freeways (1999) [3/M]. Morton also drove the couple to Nevada, where they were married in a classic kitsch Las Vegas chapel, just before flying back to Australia.

***

On July 19, Arkley and Burton returned to Melbourne, and only three days later Arkley died suddenly in his Oakleigh studio from a heroin overdose. Press coverage was intense, most of it shocked and sympathetic, although some reports tut-tutted about substance abuse, notably Susan McCulloch-Uehlin’s story in the Australian (24-25 July), which appeared only days after Arkley’s death, together with a previously prepared magazine profile on the artist, illustrated with unsympathetic photographs of him looking bleary-eyed, taken during his frantic preparations prior to leaving Australia for Venice.[7]

The artist’s funeral was held at the Monash University chapel on 30 July, under the melancholy gaze of Icon Head (1990). Several significant obituaries were published, in the Melbourne Age (Chris McAuliffe, Ashley Crawford), Bulletin (Ashley Crawford), Artlink (Tim Morrell, who curated the Venice Biennale show), Like (Robyn McKenzie), and, in 2000, Art & Australia (Ashley Crawford again): see Bibliography for details.

During the remainder of the year, Arkley’s works gradually returned from their various overseas venues, and the reality of his death began to set in. In October, as previously arranged, Zappo Head on Republic Tower (1999) [3/M] was exhibited as part of the Visual Arts program for the 1999 Melbourne International Festival. The launch, the first public event involving the artist’s work since the funeral, was a poignant affair for all involved.

At the end of the year, The Freeway (1999) was included in the Heide exhibition ‘On the Road – the Car in Australian Art’ (see Gott & Gellatly 1999). The first stirrings of art market activity also occurred, with several works offered by the major auction houses, notably Spot the Difference (Slow) 1983, sold by Sotheby’s in Melbourne (22-23 Nov.1999), in a portent of what would happen in 2000. This painting had appeared previously at auction with Sotheby’s in 1994, with an estimate of $6-8,000; in 1999, it was estimated at $15-18,000, and sold for $18,000 plus buyer’s premium.

1999 Exhibitions[8]

‘Funk-de-Siecle: out of this century’, MOMA at Heide, 6 Feb.-5 April 1999 (cur.Murray White for 1999 Woolmark Melb.Fashion Festival)

‘The Persistence of Pop’, Monash Uni.Gallery (works from the collection), 22 Feb.-24 April 1999: [9] (works from the Monash collection)

‘John Nixon: Collaborative Works’, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melb., 19 March-30 April

‘The Fabric of Labour’, Victorian Trades Hall 125th anniversary art exhibition & auction, 26 March 1999 [auction on 31 March]

Clemenger Contemporary Art Award, MOMA at Heide, April-May 1999

– refer linked entry for full details

– refer linked entry for full details

‘Howard Arkley: Drive-by Art at Republic Tower’, 299 Queen Street, from 9 October 1999 [installation photos and clippings in Arkley archive]

‘On the Road – the car in Australian art’, MOMA at Heide, 11 Dec.1999-19 March 2000 (curated by Ted Gott & Kelly Gellatly)

[1] For detailed comments on the last phase of Arkley’s life, see Spray (rev.ed., 2001), 130ff. (the new ‘Epilogue’ added to the revised edition of the book); Preston 2002: 217ff.; and Carnival 182ff.

[2] Delany & Smith 1999: 10; for further remarks on Homezone, see the editors’ introduction, pp.7-8.

[3] See Moore 1999 and Steele 1999; this project also involved Sherman Galleries director William Wright, who had arranged to pursue the idea with Arkley after his return from Venice (email correspondence with Amanda Henry, Sherman Galleries, Nov.2008).

[4] For further details, see Spray [2001]:131ff. and Preston 2002: 217ff.

[5] Raymond Gill, Age, 28/7/99

[6] Sunday Times (U.K.), 27 June 1999, pp.7-10 (clipping in Arkley’s files for 1999).

[7] See 1999 bibliography, esp.McCulloch-Uehlin (twice); see also Auty 1999, a short tribute also written for the same issue of the Australian, by the newspaper’s art critic.

[8] There was also a plan for Arkley to exhibit with Sherman Galleries (with whom he had been in discussions about resuming regular exhibitions in Sydney) at Art Chicago, Navy Pier, April-May1999, with Imants Tillers (see invitation in MUMA files, noted Sept.2002), but this did not eventuate due to HA’s Venice commitments, according to email correspondence with Amanda Henry, Sherman Galleries, Nov.2008.

[9] ‘Persistence of Pop’ reviews (clippings on file unless noted): Jeff Makin, Herald Sun 29/3/99, p.96 (describing Arkley as the ‘bard of the banal’!)